Going from 0 to 60 on GPU Programming (Part 1): Hardware & Mental Model

May 30, 2025 · 5 min read

Most articles are about finetuning models (or using them). Few are about optimizing the code that runs them. This series is a semi-organized dump of my resources and notes for learning GPU programming and intended to be a mini-resource for others that wish to break this abstraction layer.

While the idea of shifting to slightly lower level programming might seem daunting at first, knowing a few key concepts and resources can go a long way in understanding this seemingly esoteric topic.

you-can-just-do-things.jpg

Most introductions to GPUs start with this mythbuster video...

Mythbusters: GPU vs CPU; a visualization of parallel processing

It's a visualization of what parallel compute looks like, but we can do a lot better. Knowing a little more about the architecture and the hardware make-up of a GPU will help a lot with understanding why we're why make certain design choices and optimizations later.

GPU Structure

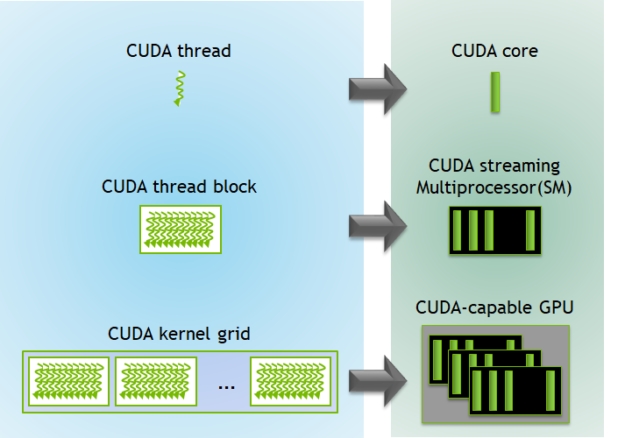

GPUs consist of many streaming multiprocessors (SMs, which are sometimes also known as compute units). These each contain "cores", schedulers, and on-chip memory (more on these later).

For now, let's start with a bottom up view of how things work on a GPU: When a program (also known as a kernel) is launched on the GPU, thousands of threads are used to execute the program in parallel. These threads are organized hierachically to match the hardware structure.

- Threads are the smallest programmable unit of execution and can each run a single instance of the kernel.

- At the hardware level, GPUs execute threads in groups of 32 called a warp. These are the effective smallest unit of execution on the GPU, meaning that if 48 threads are needed, then 2 warps/64 threads will be used. All threads in a warp have to execute the same instructions at the same time. Warps are therefore also the smallest unit of scheduling: the scheduler issues instructions one warp at a time.

- Blocks/Thread blocks are groups of warps/threads. Each block is assigned to a single SM and share its resources (memory and clock). Hence all threads within a block have access to a fast on-chip memory which they can use to share and sync data (more on this later).

- Grids are a collection of blocks, and blocks within a grid can execute independently and concurrently, depending on the available GPU resources. There are no shared resources between blocks in a grid.

GPU Kernel Execution Hierarchy

This hierarchy and organization is part abstraction and part grounded in the structure of the GPU hardware. They are necessary to begin understanding how programs are written for them. As a simplification, we write code that is executed by threads, and we use blocks/grids to run many copies of that code in parallel.

Grounding the abstraction in hardware

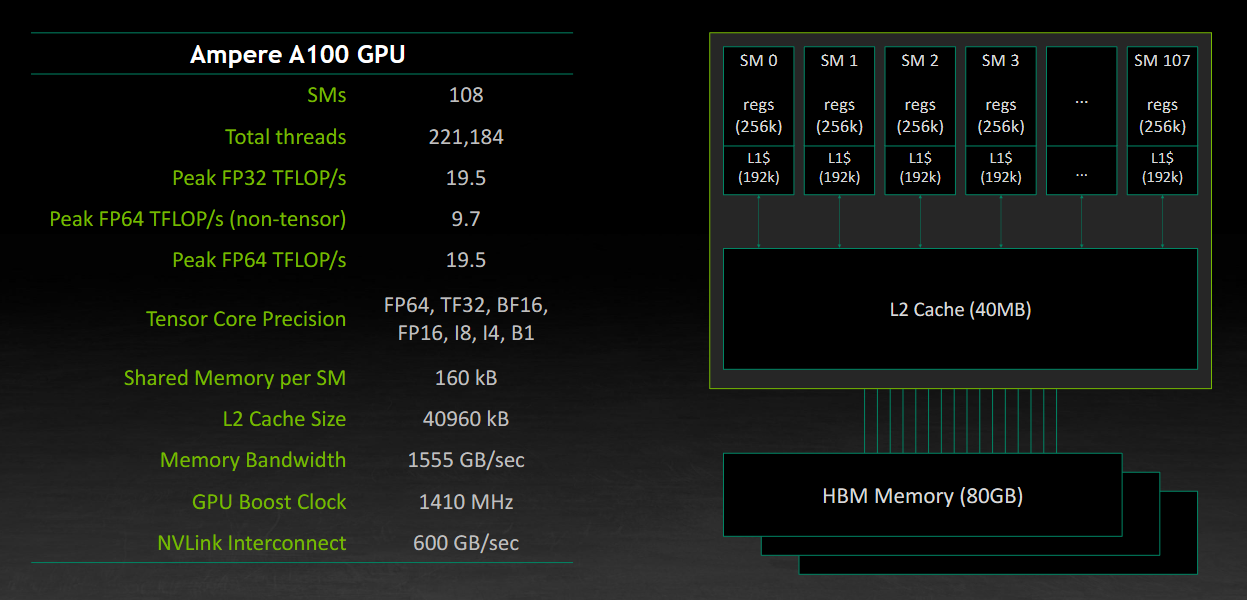

If you've ever bought a GPU or watched an NVIDIA announcement, you've probably seen something like this:

NVIDIA A100 Hardware Specifications

As mentioned earlier, each SM executes multiple warps simultaneously, scheduling instructions, and providing access to fast on-chip memory (shared memory and registers).

In terms of hardware, an SM includes:

- ALUs (integer and floating point operations)

- Tensor cores (matrix operations)

- Registers

- Shared memory

- Warp schedulers

Multiple SMs operate independently within a GPU to orchestrate thousands of concurrent threads in a GPU.

Kernel Lifecycle

A typical GPU computation involves:

- Data allocation and transfer of the input data from the host memory to device memory (GPU global memory).

- Launching the kernel (and passing it pointers to the data)

- Computation over the data using thousands of parallel threads

- Transfering the data from device memory back to host memory.

It's good to note here that kernels do not return anything. Kernels operate on pointers, referencing a position in GPU global memory where the data is located. The result of the kernel's computation is typically written to designated points in global memory.

While the idea of working with pointers might be daunting to some without a CS background, the use of pointers here is typically straightforward. It also makes it easy to write multiple outputs (including intermediate outputs) with a single kernel operation.

Summary Mental Model

- Threads are smallest unit of a GPU, they are also typically abundant

- Warps are bundles of 32 threads, the smallest execution unit

- Thread blocks allow threads to share and use fast on-chip memory

- SMs execute thread blocks

- Global memory is slow

CUDA vs Triton: Abstraction Differences

- Triton abstracts away most of the block layer and shoulders responsibility of thread-block organization. Instead, the user focuses on the the data to be managed by the threads (called "tiles"). The mapping of threads to GPU hardware is then handled by Triton based on grid size, tile dimensions, and memory requirements. Triton also handles optimization of memory allocation, allowing threads to access contiguous memory locations.

- CUDA provides more explicit control over grid and block dimensions (up to 3D), and allows explicit management of thread IDs, block IDs, and grid IDs, offering finer-grained control but requiring more manual management.

Triton allows you to reason at a higher level of abstraction: vectorized blocks, rather than individual threads. This trade-off is typically worth it and hence the hype around triton: getting 80% of the optimization performance with 20% of the work.